Posts (page 29 of 43)

-

Plugins Stand Out Mar 14, 2013

A minor theme in my recent B-Sides SF presentation was the stagnancy of innovation since HTML4 was finalized in December 1999. New programming patterns have emerged since then, only to be hobbled by the outmoded spec. To help recall that era I scoured archive.org for ancient curiosities of the last millennium – like Geocities’ announcement of 2MB (!?) of free hosting space.

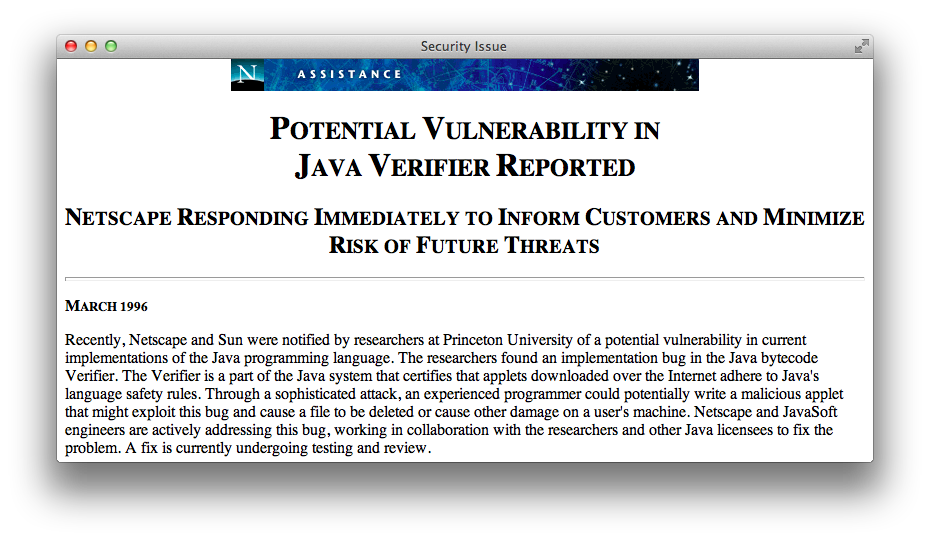

One appsec item I came across was this Netscape advisory regarding a Java bytecode vulnerability – in March 1996.

Almost twenty years later Java still plagues browsers with continuous critical patches released month after month after month, including the original date of this post – March 2013.

Java’s motto

Write once, run anywhere.

Java plugins

Write none, uninstall everywhere.

The primary complaint against browser plugins is not their legacy of security problems, although it’s an exhausting list. Nor is Java the only plugin to pick on. Flash has its own history of releasing nothing but critical updates. The greater issue is that even a secure plugin lives outside the browser’s Same Origin Policy (SOP).

When plugins exist outside the expected security and privacy controls of SOP and the DOM, they weaken the browsing experience. Plugins aren’t completely independent of these controls, their instantiation and usage with regard to the DOM still falls under the purview of SOP. However, the ways that plugins extend a browser’s network and file access are rife with security and privacy pitfalls.

For one example, Flash’s Local Storage Object was easily abused as an “evercookie” because it was unaffected by clearing browser cookies and whether browsers were configured to accept cookies or not. Even the lauded HTML5 Local Storage API could be abused in a similar manner. It’s for reasons like these that we should be as diligent about demanding privacy fixes as much as we demand security fixes.

Unlike Flash, the HTML5 Local Storage API is an open standard created by groups who review and balance the usability, security, and privacy implications of features intended to improve the browsing experience.

Creating a feature like Local Storage and aligning it with similar security controls for cookies and SOP makes them a superior implementation in terms of preserving users’ expectations about browser behavior. Instead of one vendor providing a means to extend a browser, browser vendors (the number of which is admittedly dwindling) are competing to implement a uniform standard.

Sure, HTML5 brings new risks and preserves old vuln in new and interesting ways, but a large responsibility for those weaknesses lies with developers who would misuse an HTML5 feature in the same way they might have misused AJAX in the past.

Maybe we’ll start finding poorly protected passwords in Local Storage objects, or more sophisticated XSS exploits using Web Workers or WebSockets to exfiltrate data from a compromised browser. Security ignorance takes a long time to fix. Even experienced developers are challenged by maintaining the security of complex apps.

HTML5 promises to make plugins largely obsolete. We’ll have markup to handle video, drawing, sound, more events, and more features to create engaging games and apps. Browsers will compete on the implementation and security of these features rather than be crippled by the presence of plugins out of their control.

Getting rid of plugins makes our browsers more secure, but adopting HTML5 doesn’t imply browsers and web sites become secure. There are still vulns that we can’t fix by simple application design choices like including X-Frame-Options or adopting Content Security Policy headers.

Would you click on an unknown link – better yet, scan an inscrutable QR code – with your current browser? Would you still do it with multiple tabs open to your email, bank, and social networking accounts?

You should be able to do so without hesitation. The goal of appsec, browser developers, and app owners should be secure environments that isolate vulns and minimize their impact.

It doesn’t matter if “the network is the computer” or an application lives in the cloud or it’s something as a service. It’s your browser that’s the door to web apps and, when it’s not secure, an open window to your data. Getting rid of plugins is a step towards better security.

-

RSA US 2013, ASEC-F41 Slides Mar 8, 2013

Here are the slides for my presentation, Using HTML5 WebSockets Securely, at this year’s RSA US conference in San Francisco.

It’s a continuation of the content created for last year’s BlackHat and BayThreat presentations. RSA wants slides to be in a specific template. So, these slides are less visually stimulating than I usually have the freedom to create. (RSA demands an “Apply” slide at the end. Otherwise they don’t know if you told attendees how to apply what you were talking about for the last 45 minutes.) Still, the slides should convey some useful concepts for understanding and working with WebSockets.

This is hardly the end for this topic. But there’s a long list of other material that I need to finish before this protocol gets more attention.

-

Condign Punishment Mar 5, 2013

The article rate here slowed down in February due to my preparation for B-Sides SF and RSA 2013. I even had to give a brief presentation about Hacking Web Apps at my company’s booth. (Followed by a successful book signing. Thank you!)

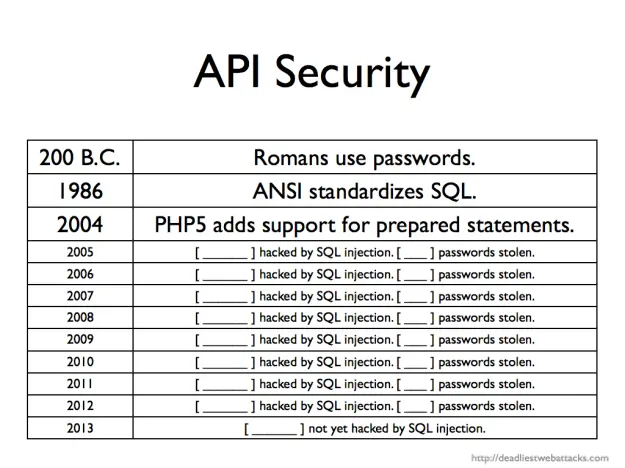

In that presentation I riffed off several topics repeated throughout this site. One topic was the mass hysteria we are forced to suffer from web sites that refuse to write safe SQL statements.

Those of you who are developers may already be familiar with a SQL-related API, though some may not be aware that the acronym stands for Advanced Persistent Ignorance.

Here’s a slide I used in the presentation (slide 13 of 29). Since I didn’t have enough time to complete nine years of research I left blanks for the audience to fill in.

Now you can fill in the last line. A security company admitted last week to a compromise that was led by a SQL injection exploit. Sigh. The good news was that no massive database of usernames and passwords (hashed or not) went walkabout. The bad news was that attackers were able to digitally sign malware with a stolen Bit9 code-signing certificates.

I don’t know what I’ll add as a fill-in-the-blank for 2014. Maybe an entry for NoSQL. After all, developers love to reuse an API. String concatenation in JavaScript is no better that doing the same for SQL.

If we can’t learn from PHP’s history in this millennium, perhaps we can look further back for more fundamental lessons. The Greek historian Polybius noted how Romans protected passwords (watchwords) in his work, Histories1:

To secure the passing round of the watchword for the night the following course is followed. One man is selected from the tenth maniple, which, in the case both of cavalry and infantry, is quartered at the ends of the road between the tents; this man is relieved from guard-duty and appears each day about sunset at the tent of the Tribune on duty, takes the tessera or wooden tablet on which the watchword is inscribed, and returns to his own maniple and delivers the wooden tablet and watchword in the presence of witnesses to the chief officer of the maniple next his own; he in the same way to the officer of the next, and so on, until it arrives at the first maniple stationed next the Tribunes. These men are obliged to deliver the tablet (tessera) to the Tribunes before dark.

More importantly, the Romans included a consequence for violating the security of this process:

If they are all handed in, the Tribune knows that the watchword has been delivered to all, and has passed through all the ranks back to his hands: but if any one is missing, he at once investigates the matter; for he knows by the marks on the tablets from which division of the army the tablet has not appeared; and the man who is discovered to be responsible for its non-appearance is visited with condign punishment.

We truly need a fitting penalty for SQL injection vulnerabilities; perhaps only tempered by the judicious use of salted, hashed passwords.

-

Polybius, Histories, trans. Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (London, New York: Macmillan, 1889), Perseus Digital Library. https://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0543.tlg001.perseus-eng1:6.34 (accessed March 5, 2013). ↩

-