Posts (page 15 of 43)

-

DevSecCon London 2017 Oct 20, 2017

Ah, London — the city responsible for most of my music collection. Also, the city where I recently had the fortune to present at DevSecCon.

DevSecCon examines the challenges facing DevSecOps (and DevOps) practitioners. It emphasizes how to work with people to make tools and process part of the CI/CD pipeline. This resonates with me greatly because I strongly believe that effective security comes from participation and empathy.

DevSecOps brings security teams into the difficult tasks of writing, supporting, and maintaining code. It’s a welcome departure from delivering a “Go fix this” message. Sometimes developers need guidance on basic security principles and an introduction to the OWASP Top 10. Sometimes developers have that knowledge and are making tough engineering choices between conflicting recommendations. Security shouldn’t be the party that says, “No”. Their response should be, “Here’s a way to do that more securely.”

The “Go fix this” attitude has underserved appsec. We live in an age of 130,000+ Unicode characters and extensive emoji. Yet developers must still (for the most part) handle apostrophes and angle brackets as special exceptions lest their code suffer from HTML injection, cross-site scripting, or a range of other injection-based flaws.

All this is to say, check out The Flaws in Hordes, the Security in Crowds, which explores this from the perspective of vuln discovery — and that too much investment in vuln discovery at the time when an app reaches production misses the chance to build stronger foundations.

Slides from all the presentations are available here.

-

Bikeshredding & Threat Models Oct 1, 2017

Asking a DevOps team what they’re most worried about in their app is a great way to seed a conversation about risk. In my recent presentations, I’ve taken to emphasizing the use of threat modeling exercises as an avenue towards security awareness. Threat models are ways of reasoning about different ways an app’s data or users might be compromised. They can also be great ways to build security awareness by encouraging creative thinking about an app’s security in a way that drives constructive conversation and minimizes judgement about lack of security knowledge.

A penny-farthing for your threat models. A key element to such discussions is using the “Yes, and…” principle, in which you guide the conversation not by negating someone’s ideas, but expanding on them or offering an alternative viewpoint. In this exercise, you are the security expert filling in gaps in knowledge and nudging tangents away from unlikely scenarios, but letting the DevOps team drive the discussion amongst themselves.

Bikeshredding is when this exercise devolves into distraction. The term echoes “bikeshedding” — a situation where a software engineering discussion becomes overwhelmed by details irrelevant to the problem at hand. For example, if your problem relates to efficient structures for storing bicycles, it’s unlikely that the color of the structure contributes meaningfully to that efficiency. And that such ill-timed attention is counterproductive to the core task. It may also be as much about arguing over subjective choices as it may be about misusing data as an illusion about objective preferences.

In bikeshredding, a threat model becomes disjoined from reality. It may represent a scenario unduly influenced by ideology or one based on incomplete (or ignored) information.

A strong indicator of bikeshredding are models that begin with “Assuming…” or “All you need to do is…”. For example, “Assuming the Same Origin Policy is broken, then…“ it may not be necessary to continue this sentence if it involves a discussion of cross-site scripting or anti-CSRF tokens. Or perhaps the setup to an attack “just requires a DNS or BGP hijack” before the vuln under discussion could be exploited.

That doesn’t mean such scenarios aren’t impossible or that they should be dismissed. It does mean that threats are not unbounded agents that visit great woe unto apps or networks. Threat actors (those executing an attack) require resources and preparation. In some cases, those resources and prep may be nothing more than a browser bar and an unvalidated URL parameter. In other cases, those costs or sequence of events may be high and complex.

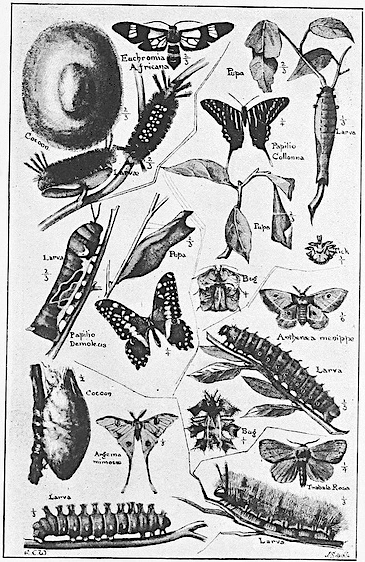

There is a place for stunt hacks, where an SDR Bluetooth spoofer affixed to a hedgehog launched (safely, with parachute) from a drone hacks an IoT fridge in order to obtain some tasty insects stored therein. Tinkering and creativity are fun. Always educational, it can sometimes inform practical appsec.

But there’s a reason that legacy systems and legacy software are notorious attack vectors. They’re easy and cost little for the attacker.

As you mature your organization’s stance and have more robust ways to respond to threats, you’ll also increase the time and resources required of an attacker. Over time, you’ll understand how successful attacks are executed. And, although you’ll continue to improve your app’s baseline security to prevent exploits, it’s highly likely that you’ll discover that an efficient detection and response becomes an equally important investment.

Use threat models to spread security knowledge throughout a DevOps team and engage them in prioritizing countermeasures and containment. Help them be informed about security topics and the chain of events necessary for various attacks to succeed. Avoid the bikeshredding and let them build the structure that handles user data with minimal risk.

-

ISC2 Security Congress, 4416 - GBU Slides Sep 29, 2017

My presentation on the good, the bad, and the ugly about crowdsourced security continues to evolve. The title, of course, references Sergio Leone’s epic western. But the presentation isn’t a lazy metaphor based on a few words of the movie. The movie is far richer than that, showing conflicting motivations and shifting alliances.

The presentation is about building alliances, especially when you’re working with crowds of uncertain trust or motivations that don’t fully align with yours. It shows how to define metrics and use them to guide decisions.

Ultimately, it’s about reducing risk. Just chasing bugs isn’t a security strategy. Nor is waiting for an enumeration of vulns in production a security exercise. Reducing risk requires making the effort to understand what what you’re trying to protect, measuring how that risk changes over time, and choosing where to invest to be most effective at lowering that risk. A lot of this boils down to DevOps ideals like feedback loops, automation, and flexibility to respond to situations quickly. DevOps has the principles to support security, it should have to knowledge and tools to apply it.